“You need to rest after an injury.” While in general this advice is true, what if there was a way to rebuild or at the very least maintain your muscle after an injury? A way to put a healthy amount of stress through your tissues that allows you to return to the field quicker?

You may think this is a cheat code, or “bio-hacking” but in truth it’s simpler than that. It is the secret that is used in professional athlete training rooms across the globe - Blood Flow Restriction Training (BFR).

What is BFR?

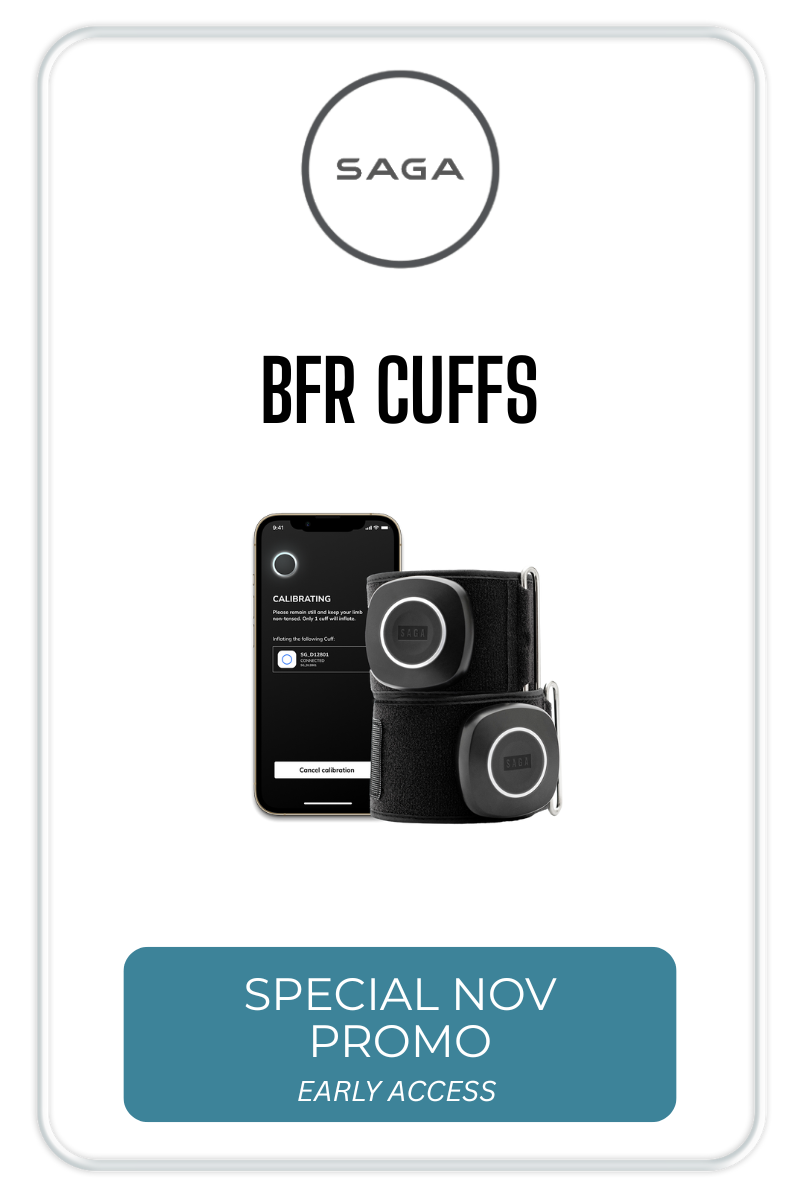

It’s not magic, it’s occlusion. Specialized cuffs, similar to blood pressure cuffs, are wrapped around the upper portion of your arms or legs and inflated to 40%-90% of your arterial occlusion pressure. This partially restricts the blow of blood into your limbs as you perform your exercise.

The restriction of blood tricks your muscles into believing they are working harder; allowing you to benefit more from working at much lower, and safer, loads (20%-30% of 1RM)[2,3]. The metabolic effects from working out with BFR at 30% 1RM have been shown to provide similar results as working out at 70% 1RM. Thus, making training while recovering safer during early rehab. [4]

The Secret? Metabolic Activity

Muscle growth depends on the nutrients being delivered to build up bigger, faster, and stronger. BFR creates metabolic stress within the muscle which causes lactate accumulation, cellular swelling, and activation of growth pathways. [3]

Using BFR also enhances type II, fast twitch, muscle recruitment while also promoting new blood vessel formation to help fuel those muscles. [2,3,5]

It’s tricking your body into thinking it’s working harder than it really is.

Why do Pro Athletes use this technique?

Sports aren’t just a game to professional athletes, it’s a way of life. Downtime from an injury affects more than just their playing time and muscle atrophy can delay the return to play. Here are a few advantages of using BFR during rehab:

Preserve muscle mass [6,7]

Reduce mechanical stress on healing tissue [4]

Accelerate recovery timelines, returning athletes to the field sooner [6]

Safe early rehab option when protocols and precautions are followed [8]

PRODUCTS WE LOVE

While technique and programming drive effective Blood Flow Restriction Training, the right equipment plays a key supporting role. We consistently use and recommend SAGA and VALD BFR cuffs for their precision, safety, and reliability. When applied appropriately, these systems allow athletes to train at lower loads while still creating the metabolic stimulus needed to preserve muscle and support a safe return to play.

Is it safe?

In general, yes BFR is safe to use when applied properly and under the supervision of a trained professional. A qualified provider should screen an athlete for any complications that could cause issues.

Cardiovascular issues like a history of blood clots, severe hypertension, vascular issues, active infections, and cancer are all contraindications.

What does a training program look like with BFR?

Athletes should look to train 2-3 times a week, but more than 3 times a week has shown favorable outcomes. [10]

Cuff should be inflated to ≥160 mmHg or 40-90% of arterial occlusion pressure

Select a weight that is 20%-30% of 1RM

1-3 exercises are selected to be performed with the cuff inflated

An example repetition protocol would be [4]

30 reps

Rest 30 seconds

15 reps

Rest 30 seconds

15 reps

Rest 30 seconds

15 reps

Do I need to be a professional athlete to use BFR?

No! BFR is a valid treatment option for anyone looking to supplement their current workout, or utilize while injured. Some great options for adding in BFR include[12,3]:

Adding BFR work at the end of regular strength sessions for additional volume without excessive fatigue

Using BFR during taper periods to maintain muscle mass while reducing mechanical load

Incorporating BFR during in-season training when recovery demands are high

Before starting any BFR training it is important to consult with your healthcare provider, proper screening is essential for safe implementation.

References

Blood Flow Restriction Therapy After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Johns WL, Vadhera AS, Hammoud S. Arthroscopy : The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery : Official Publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2024;40(6):1724-1726. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2024.03.004.

Blood Flow Restriction Therapy: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Vopat BG, Vopat LM, Bechtold MM, Hodge KA. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2020;28(12):e493-e500. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00347.

Physiological Adaptations and Practical Efficacy of Different Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Training Modes in Athletic Populations. He C, Zhu D, Hu Y. Frontiers in Physiology. 2025;16:1683442. doi:10.3389/fphys.2025.1683442.

Blood Flow Restriction Training. Lorenz DS, Bailey L, Wilk KE, et al. Journal of Athletic Training. 2021;56(9):937-944. doi:10.4085/418-20.

Blood Flow Restriction Training and the High-Performance Athlete: Science to Application. Pignanelli C, Christiansen D, Burr JF. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2021;130(4):1163-1170. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00982.2020.

Time to Save Time: Beneficial Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training and the Need to Quantify the Time Potentially Saved by Its Application During Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. Bielitzki R, Behrendt T, Behrens M, Schega L. Physical Therapy. 2021;101(10):pzab172. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzab172.

Editorial Commentary: Blood Flow Restriction Therapy Continues to Prove Effective. LaPrade RF, Monson JK, Schoenecker J. Arthroscopy : The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery : Official Publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2021;37(9):2870-2872. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2021.04.073.

The Safety of Blood Flow Restriction Training as a Therapeutic Intervention for Patients With Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Systematic Review. Minniti MC, Statkevich AP, Kelly RL, et al. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;48(7):1773-1785. doi:10.1177/0363546519882652.

Comparison of Blood Flow Restriction Interventions to Standard Rehabilitation After an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Systematic Review. Colombo V, Valenčič T, Steiner K, et al. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2024;52(14):3641-3650. doi:10.1177/03635465241232002.

Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training on Physical Fitness Among Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Yang K, Chee CS, Abdul Kahar J, et al. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):16615. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-67181-9.

Application of Blood Flow Restriction Training in Adolescents: A Narrative Review. Chen ZL, Zhao TS, Ren SF, et al. Medicine. 2025;104(29):e43084. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000043084.

Where Does Blood Flow Restriction Fit in the Toolbox of Athletic Development? A Narrative Review of the Proposed Mechanisms and Potential Applications. Davids CJ, Roberts LA, Bjørnsen T, et al. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2023;53(11):2077-2093. doi:10.1007/s40279-023-01900-6.

A Useful Blood Flow Restriction Training Risk Stratification for Exercise and Rehabilitation. Nascimento DDC, Rolnick N, Neto IVS, Severin R, Beal FLR. Frontiers in Physiology. 2022;13:808622. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.808622.